1. Cinéma:

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

Naturally the country that invented cinema must have invented the word for it. “Cinéma,” was originally shortened

from the word “cinématographe,” which was a French derivative of the Greek compound “kinematographos,” kinema

meaning movement, and grapho meaning to write or record, as such cinema is simply recorded movement.

2. Avant-garde:

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

In French, Avant-Garde means “the forefront,” and it retains a similar usage in English, though it refers quite

specifically to a relatively ambiguous forefront that is usually implicated in alternative trends, such as an

“avant-garde,” art show, that could portray an artist as positioned at the forefront, but the forefront of exactly

what discipline or movement remains undefined.

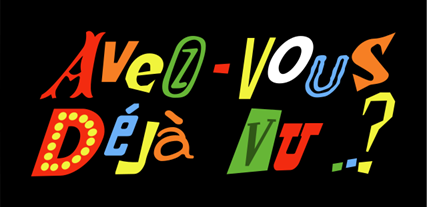

3. Déjà vu:

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

Stop me if you think you’ve seen this one before! Déjà vu, in French, means “already seen,” employing the adverb

“déjà,” already, and the past participle of “voir,” to see, “vu”. The term also refers to a condition in which one

feels one is seeing, or experiencing something they believe they have seen or experienced before but cannot place

when or where. Déjà vu is similarly used in France to denote this peculiar feeling.

4. Garage:

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

This innocuous everyday word is French! Derived from the French verb “garer,” meaning “to shelter,” the term

“garage,” came into use in the early 20th century to describe a variety of facilities used to maintain, fix, and

store vehicles, particularly automobiles.

5. Arcade:

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

In French, an arcade refers to a covered street or alley lined with shops, hence the arcades at Les Halles which

were torn down in the 1970s, and Walter Benjamin’s unfinished work, “The Arcades Project,” which detailed Parisian

arcades in the 19th century. By stark contrast, in English, an arcade is a place to gather and play video games.

6. Impasse:

The French meaning of impasse is a dead end at the end of a road, or path. It also shares the English meaning which

connotes an irresolvable problem or situation with no solution.

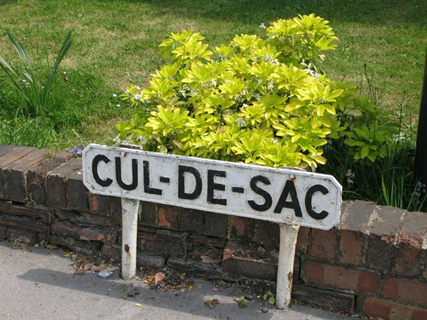

7. Cul-de-sac:

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

In French, a Cul-de-sac refers to a dead end street while in English it refers to a dead end street lined with

houses.

8. Bas-relief:

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

A bas-relief, a low-relief, this word is actually Italian in origin, basso-relievo but adapted to French and

thereafter incorporated into English. The Italian term derives from a chiseling details onto two dimensional works

of art and accentuating their features, such as the indentations in a crown, in a face, or on a chariot, with the

intention of affording these pieces the illusion of being three dimensional. This technique featured prominently in

Greek and Roman architecture as is evident in the bas-relief frieze on the Parthenon at Athens. It was also

incredibly popular in architecture from the 5th century through the Medieval period and was a paean of luxury

architecture during the Renaissance hence its translation from Italian to French, as the popular architecture of the

Italian Renaissance was transmuted to the French Renaissance. Bas-reliefs remained indications of authority and

luxury through the 19th century and were a staple in imperial British architecture as well, as such the French name

carried over.

9. Film Noir:

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons (Big Combo movie).

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons (Big Combo movie).

The term Film Noir was used by French critics to describe a cynical, hardboiled movement and contested genre in

American cinema arguably starting with “The Maltese Falcon,” (1941) and “Double Indemnity,” (1944). Influenced by

German Expressionism of the 1910s-1920s, Film Noir features low-key lighting, unbalanced compositions, and a host of

stock characters such as the surly anti-hero private eye, the scorching femme fatale, and the invariably over

confident police who interrupt the all consuming work of the private eye.

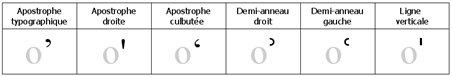

10. Apostrophe:

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

Stop me if you think you’ve seen this one before! Déjà vu, in French, means “already seen,” employing the adverb

“déjà,” already, and the past participle of “voir,” to see, “vu”. The term also refers to a condition in which one

feels one is seeing, or experiencing something they believe they have seen or experienced before but cannot place

when or where. Déjà vu is similarly used in France to denote this peculiar feeling.

11. En route:

To tell someone you’re en route, is the same in French as it is in English, and was adapted to English when French

was the chosen language of the British upper class who had the privilege to travel and thus be “en route”.

12. Entrepreneur:

The word “entrepreneur,” possesses the same definition in both languages and is derived from a 13th century French

verb meaning “to do something,” or “to undertake.”

13. Bizarre:

In French bizarre is often used as an equivalent for the English word “weird,” whereas, bizarre in English often

refers to something more specifically, inexplicably strange.

14. Simple:

The French and English meanings are equivalent with the word “simple,” as both connote easiness, naivety, or

plainness. The primary difference, once again, is the pronunciation.

15. Cliché:

In French the meaning of cliché depends upon the context, it can either refer to a snapshot, like “10 Clichés de

Brigitte Bardot pendant les années 60”, or, like the English usage, stereotypes and worn out tropes.